Biologists Uncover Mechanisms for Cholera Toxin’s Deadly Effects

September 11, 2013

By Kim McDonald

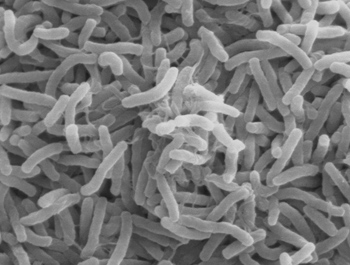

Cholera toxin is produced by the highly infectious bacterium Vibrio cholerae.

Wikipedia Commons

Biologists at the University of California, San Diego have identified an underlying biochemical mechanism that helps make cholera toxin so deadly, often resulting in life-threating diarrhea that causes people to lose as much as half of their body fluids in a single day.

Two groups of scientists working on fruit flies, mice and cultured human intestinal cells studied cholera toxin, produced by the highly infectious bacterium Vibrio cholerae. They discovered the toxin exerts some of its devastating effects by reducing the delivery of proteins to molecular junctions that normally act like Velcro to hold intestinal cells together in the outer lining of the gut.

Their findings, published in the September 11 issue of the journal Cell Host & Microbe, could guide the development of new therapies against the deadly disease, which threatens millions of people in poor countries around the world who live in areas with poor sanitation, with water supplies frequently contaminated by the cholera bacterium. The worst cholera epidemic in recent history occurred after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, killing more than 7,900 people and hospitalizing hundreds of thousands in Haiti and in the neighboring Dominican Republic.

“We uncovered a mechanism by which cholera toxin disrupts junctions that normally zip intestinal epithelial cells together into a tight sheet, which acts as a barrier between the body and intestinal content,” said Ethan Bier, a professor of biology at UC San Diego who headed one of the two teams. “A consequence of these weakened cell junctions is that sodium ions and water can escape between cells and empty into the gut.”

The worst cholera epidemic in recent history occurred after the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, killing more than 7,900 people.

Wikipedia Commons

The study built on research published decades ago, when scientists discovered that cholera toxin caused the overproduction of small chemical messenger molecule, cyclic adenosine monophosphate, or “cAMP,” in epithelial cells lining the intestine.

“High levels of cAMP activate a protein channel called CFTR that allows the negatively-charged chloride ions to rush out of intestinal epithelial cells into the contents of the gut,” said Victor Nizet, MD, a professor of pediatrics and pharmacy at UC San Diego School of Medicine, who headed the other team. “Through basic physiological principals known as electroneutrality and osmotic balance, these secreted chloride ions must be accompanied by positively-charged sodium ions and water, altogether leading to a profuse loss of salt and water in the diarrheal stools.”

Media Contact: Kim McDonald (858) 534-7572, kmcdonald@ucsd.edu

Comment: Ethan Bier (858) 534-8792, ebier@ucsd.edu