Extinction Runs in the Family

AUGUST 3, 2009

By Susan Brown

Global calamities like the one that doomed most dinosaurs forever alter the varieties of life found on Earth. But new research shows that it doesn't take a catastrophe to end entire lineages.

Survivors. Venus clams, a large family with more than 500 living species, made it through the most recent mass extinction.

Credit: K.J. McClure, College of William and Mary

An analysis of 200 million years of history for marine clams found that vulnerability to extinction runs in evolutionary families, even when the losses result from ongoing, background rates of extinction.

"Biologists have long suspected that the evolutionary history of species and lineages play a big role in determining their vulnerability to extinction, with some branches of the tree of life being more extinction-prone than others," said Kaustuv Roy, a biology professor at the University of California, San Diego, noting that human activities threaten some evolutionary lineages of living vertebrates more than others. "Now we know that such differential loss is not restricted to extinctions driven by us but is a general feature of the extinction process itself."

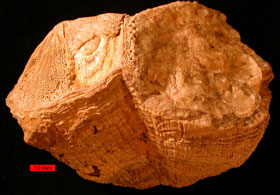

Lost. In an earlier age, these marine bivalves called rudists were so abundant they formed reefs. Rudists vanished in the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period.

Credit: Mark A. Wilson, The College of Wooster

Roy and colleagues Gene Hunt of the Smithsonian Institution and David Jablonski of the University of Chicago report their findings in the August 7 issue of Science.

Their study focused on marine bivalves such as clams, oysters, mussels and scallops, whose tough shells fossilize well to provide a rich record for study. By analyzing a global database of bivalve fossils stretching from the Jurassic Period to the present, the researchers noted when each genus disappeared and whether their relatives disappeared at the same time.

On average, closely related clusters of clams vanished together more often than expected by chance.

"Both background extinctions, which represent most extinctions in the history of life, and mass extinctions tend to be clumped into particular evolutionary lineages," Jablonski said.

The effect was particularly strong during the mass extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period, when clam lineages with the highest "background" rates of extinction during more normal times were hardest hit. Three families with the highest background rates disappeared entirely. Two others, with rates more than twice the median, suffered heavy losses and have not recovered to this day.

"Big extinctions have a filtering effect. They tend to preferentially cull the more vulnerable lineages, leaving the resistant ones to proliferate afterwards," Hunt said.

When extinctions are scattered randomly across the evolutionary tree, the breadth of evolutionary history remains represented among living things, even when many species are lost. Clumped extinctions do the opposite, disproportionately removing the deeper history.

"Extinctions in the past and presumably in the future will lop off chunks of evolutionary trees, not just prune the trees and leave most of the history intact," Jablonski said.

The message for conservation is to focus efforts on vulnerable lineages, the authors say. To preserve the full spectrum of evolutionary history found among living things today, the most fragile families will need careful protection.

Even relatively low levels of threat could eliminate large limbs, Roy said. "If you have whole lineages more vulnerable than others, then very soon, even with relatively moderate levels of extinction, you start to lose a lot of evolutionary history."

This research was funded by a grant from NASA.

Media Contact:- Susan Brown, 858-246-0161 or sdbrown@ucsd.edu

- Kaustuv Roy, kroy@ucsd.edu